SUMMARY

Fiscal rules, which are quantitative targets that restrict basic budget aggregates, have become increasingly widespread in the last 20 years. In this context, 105 economies around the world have at least one fiscal rule. However, Türkiye, which does not have a clear legally defined fiscal rule, differs from international practices. Moreover, although a draft law on fiscal rule was brought to the parliamentary agenda in 2010, it was not enacted. However, as shown in the study conducted for the Centre for Policy and Research on Turkey (Research Turkey), if the fiscal rule had been implemented, it would have been possible to prevent the deterioration observed in the budget, especially starting from 2016. This study criticizes as an unsustainable problem the fact that regulations in the current fiscal legislation, such as the borrowing limit, which are not fiscal rules but are intended to ensure budget discipline, are frequently overcome by temporary law articles. In order to overcome this problem, it is suggested as a public policy recommendation that the fiscal rule should be supported by a fiscal council in line with international practices in the event of a possible transition to a rule-based economy.

The Need for Fiscal Rule in Türkiye in the Light of International Experiences and the Failed Fiscal Rule Initiative

1. Introduction

Although the ratio of central government debt stock to GDP is not relatively high in Türkiye, the nominal debt stock has been on a rapid upward trend since 2018. On the other hand, in the last five years, domestic borrowing in foreign currency resumed, the share of floating rate debt in the stock increased and the riskiness of the debt portfolio increased (Cangöz, 2022). This decline in the quality of government debt is a consequence of institutional changes in debt management (Cangöz, 2019) and the decline in discipline and predictability in public finance in general (Cangöz, 2021). In addition, extra-budgetary fiscal risks, particularly Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) projects, Credit Guarantee Fund (CGF) and Currency Hedged Deposits (FXP), have been on the rise. In this context, conducting public financial management in line with measurable targets (rules) set by legal regulations will contribute to financial stability and economic sustainability as well as transparency and predictability.

International practices show that fiscal rules have become widespread in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, with a particular focus on the budget deficit/GDP ratio and the debt stock/GDP ratio. In parallel with the widespread adoption of rule-based public finance, an increasing number of countries have established fiscal councils to monitor the fiscal rule and to transparently assess and report on the fiscal performance of governments.

This study evaluates the role and basic characteristics of the fiscal rule within the rule-based economic policy, whether there are regulations that qualify as fiscal rules within the existing legal framework in Türkiye, to what extent the budget deficits calculated on the basis of the Fiscal Rule Draft Law that Türkiye tried to implement in 2010 and this Draft Law are consistent with the actual budget deficits, the role of the fiscal council in the implementation of fiscal rules based on international practices and how Türkiye should structure a rule-based fiscal economy.

2.Fiscal Rule and International Practices

The introduction of certain constitutional and/or legal limitations in the implementation of economic policies is called “rule-based economic policy”, which has its theoretical foundations in the discussions on Institutional Economics and Constitutional Economics developed by the Freiburg School of Law and Economics (Aktan, Dileyici and Özen, 2010). In this context, the discretionary powers of political powers in the field of economic policy are restricted through rules on fiscal and monetary policy instruments.

Fiscal policy rules are long-term constraints that impose quantitative limits on budget aggregates. In general, they can be determined with respect to one or more of budget expenditures, budget revenues, budget balance and debt stock (IMF, 2009). A fiscal rule defines numerical targets that constrain key budget aggregates (Kopits and Symansky1998, Shick 2010). OECD (2013) defines a fiscal rule as a long-term constraint on fiscal policy through numerical limits on budget aggregates.

The constraints under the fiscal rule bind the political decisions taken by the legislature and the executive branch, while serving as a measurable and binding indicator of the executive’s fiscal management (OECD, 2103). On the other hand, fiscal rules can be valid on a national scale, but they can also be determined by supranational structures such as the European Union, and they can be binding for member countries in economic and monetary unions involving a large number of countries.

Regardless of whether they are nationally or internationally determined, fiscal rules help governments achieve fiscal targets and discipline, but there is no single rule that applies to all countries. Nevertheless, IMF (2009) states that a fiscal rule should include the following three components:

– A clear and stable link between the numerical target and the ultimate objective of public debt sustainability.

– At a minimum, the rule should provide sufficient flexibility to respond to shocks so as not to exacerbate adverse macroeconomic effects. Depending on country circumstances, the rule may need flexibility to respond to output, inflation, interest rate and exchange rate volatility, and other unforeseen shocks (e.g. natural disasters). However, it is important to be clear about the shocks that may require flexibility.

– Include a clear institutional mechanism for taking corrective actions for deviations from quantitative targets. This should include a mechanism that requires correction of past deviations within a well-defined timeframe, increases the cost of deviations in a way that incentivizes avoidance, and includes an implementation procedure for how the correction will be made.

Fiscal rules on budget deficit, budget expenditures, borrowing and debt stock are widely used for their simplicity, clarity and ease of monitoring, as well as their effectiveness in constraining and controlling public financial management. However, in recent years, fiscal rules on budget balance that take into account cyclical fluctuations have been established by taking into account the state’s duty to stabilize the economy. In this context, cyclically adjusted deficit limits have been formulated in such a way as to require the government to pursue a consistent budget policy when the structural balance is weaker. However, difficulties in assessing the output gap, delays in monitoring and reporting the fiscal rule, and difficulties in communicating with the public have resulted in the gradual decline of cyclically adjusted fiscal rules (Davoodi, Elger, Fotiou, Garcia-Macia, Han, Lagerborg, Lam, and Medas, 2022).

Fiscal rules have become widespread especially in the last 20 years in order to secure the right to budget, to implement fiscal discipline in a permanent manner independent of governments, to eliminate uncertainties arising from fiscal policy, and to ensure that public financial management is compatible with the principles of transparency and accountability.

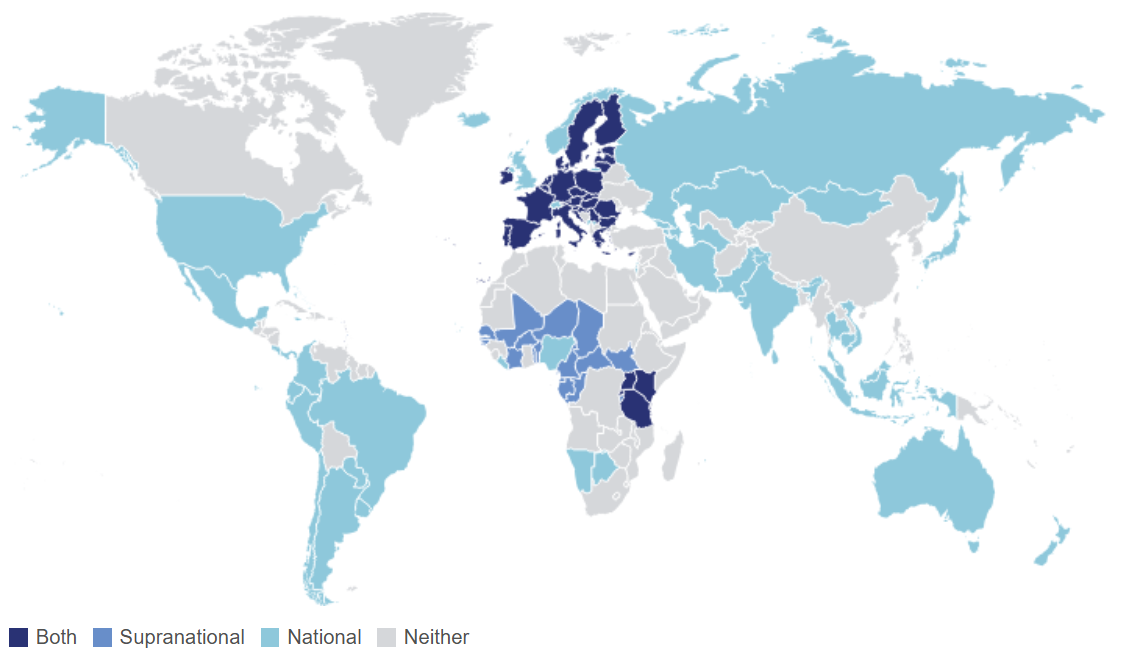

Fiscal rules, which were first introduced in advanced economies, have been increasingly adopted by developing countries and emerging economies over time. According to the IMF fiscal rule dataset, countries with fiscal rules have three different fiscal rules on average. In this context, 93 countries have fiscal rules on budget balance, 85 countries on debt stock, 55 countries on budget expenditures and 17 countries on budget revenues. The most common rules are a combination of a debt rule with operational limits on budget expenditures and/or the budget balance. In fact, according to IMF data, 105 economies have at least one fiscal rule in place by the end of 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Countries Implementing Fiscal Rules (2021)

Source: IMF, Fiscal Rules Dataset,

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/map/map.htm

In general, the legal basis for fiscal rules is a national constitution, a budget framework law or a fiscal responsibility law, and international agreements in structures such as the European Union, the West African Economic and Monetary Union, the Central African Economic and Monetary Community, the East African Economic and Monetary Union and the Eastern Caribbean Monetary Union.

Most countries with fiscal rules have formal enforcement mechanisms. These mechanisms, which usually require fiscal rules to be integrated into the annual budget and medium-term fiscal framework and hold the government accountable for fiscal rule compliance, also include measures and corrective actions to be taken by governments in case of a deviation from the fiscal rule.

3.Türkiye’s Failed Fiscal Rule Transition Attempt

Fiscal policy in Türkiye is based on Article 161 of the Constitution on the budget and the final account, but this article mainly covers the principles regarding the preparation, presentation and discussion of the budget and the final account. Therefore, the Constitution does not provide a framework for the objectives and basic principles of fiscal policy. In this context, governments have the flexibility to formulate and implement their economic and fiscal policy preferences within a wide scope of initiative, provided that they prepare the budget annually and submit it to the Parliament in accordance with the specified deadlines and forms.

The principles regarding the budget and financial control are regulated by the Public Financial Management and Control Law No. 5018. In addition, Law No. 4749 on the Regulation of Public Finance and Debt Management covers domestic and external debt, cash management and guarantees.

In Türkiye, there is no fiscal rule as defined above and in line with the practices in other countries in both the Constitution and the basic laws on public finance. However, even though it is not a fiscal rule, some limitations on borrowing have been introduced by Law No. 4749. In this context, the following arrangements have been made with Article 5 of the Law:

– Net borrowing limit: Net debt can be borrowed up to the amount of the difference between the total initial appropriations specified in the budget law of the year and the estimated revenues. The borrowing limit cannot be changed. However, taking into account the needs and development of debt management, this limit may be increased by a maximum of five percent during the year. In cases where this amount is not sufficient, an additional five percent can only be increased by a Presidential decree. In case the budget is balanced, borrowing can be increased up to a maximum of five percent of the principal payment.

– Limit on Government Domestic Debt Securities to be issued on credit: The limit of special-issue Government domestic debt securities to be issued on credit during the fiscal year shall be determined annually by the budget laws.

– Guarantee limit: The guaranteed facility to be provided in the fiscal year (Treasury repayment guarantee, Treasury investment guarantee, Treasury counter guarantee and Treasury sovereign guarantee or each of them individually) shall be determined by the budget law of the year.

– External debt rollover limit: The limit of external debt substitution to be provided within the fiscal year shall be determined by the budget law of the year

Similar to Law No. 4749’s limitations on government debt, Article 68 of the Law No. 5393 on Municipalities regulates municipal debt. In this context, it is stipulated that the external debt obtained by municipalities can only be used to finance investment projects and the domestic and external debt stock, including interest, cannot exceed the total budget revenues in municipalities and one and a half times the revenues in metropolitan municipalities.

Although both Laws No. 4749 and 5393 contain debt limitations, they do not qualify as fiscal rules because they are not directly related to the ultimate objective of sustainability, do not contain clear provisions on the definition of external shocks and providing flexibility against these shocks, and do not specify corrective mechanisms. However, these regulations can be considered as restrictive measures that support fiscal discipline.

In Türkiye, there is no fiscal rule and there is no sanction mechanism even in case of significant deviations from budget targets, and governments are only politically accountable. Especially after the transition to the presidential system in 2018, the government’s flexibility in fiscal policy formulation and budget execution has increased even more with the restriction of the TGNA’s budget control authority. In fact, governments with a sufficient majority in the TGNA have expanded their spending authority by amending the borrowing limit in Law No. 4749 five times in the last seven years, in 2017, 2019, 2020, 2022 and 2023. Therefore, the borrowing limit alone has not been sufficient to ensure budget discipline and accountability. Moreover, no corrective measures were envisaged when increasing the borrowing limit through temporary articles in Law No. 4749.

In 2010, the government of the time brought a fiscal rule bill to the agenda of the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye, taking into account the conjuncture effect, in view of the fact that the provisions in Laws No. 4749 and 5393 did not qualify as fiscal rules. While the fiscal rule in the draft law was defined as the ratio of the general government deficit to GDP, it was formulated as follows, taking into account how far the actual deficit in the previous year was from the medium-long term target and the impact of the business cycle:

a(t) a(t-1) – y (a(t-1)– a*) – k (b(t) – b*)

In the formula in the draft law;

a(t): the ratio of general government deficit to gross domestic product in the current year,

a(t-1): the ratio of general government deficit to gross domestic product in the previous year,

a*: the targeted value of the ratio of general government deficit to gross domestic product in the medium to long term in order to reduce the debt stock to a reasonable level, set at one percent,

b(t): the rate of increase in real gross domestic product in the current year,

b: the threshold real gross domestic product growth rate to be taken as basis in the operation of automatic stabilizers, set as five percent

y: convergence speed coefficient

k: coefficient reflecting the cyclical effect,

– y (a(t-1)-a*) : open effect

– k (b(t) – b*) : cyclical effect

was used to express the deficit effect.

The coefficient (y) used for the deficit effect, which indicates the rate of convergence to the target when there is a deviation from the medium-long term target (one percent) in any given year, was set as 0.33 by the Draft Law. Thus, it was envisaged that approximately thirty-three percent of the amount deviated from the target would be compensated in the following year.

The coefficient (k) used for the cyclical effect showed how much savings would be made for each percentage point of growth in real GDP above 5 percent and how much deficit would be incurred for each percentage point of growth below 5 percent. Thus, the fiscal rule was intended to be countercyclical, providing flexibility to fiscal policy during periods of real economic growth and contraction. The coefficient k, which has a negative sign in the formula, was envisaged to support the working mechanism of automatic stabilizers by reacting countercyclically to business cycles.

However, the Fiscal Rule Draft Law was withdrawn by the ruling party at the plenary session of the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye after the discussions in the commission and was not enacted into law. Thus, Türkiye’s attempt to transition to a rule-based fiscal policy failed.

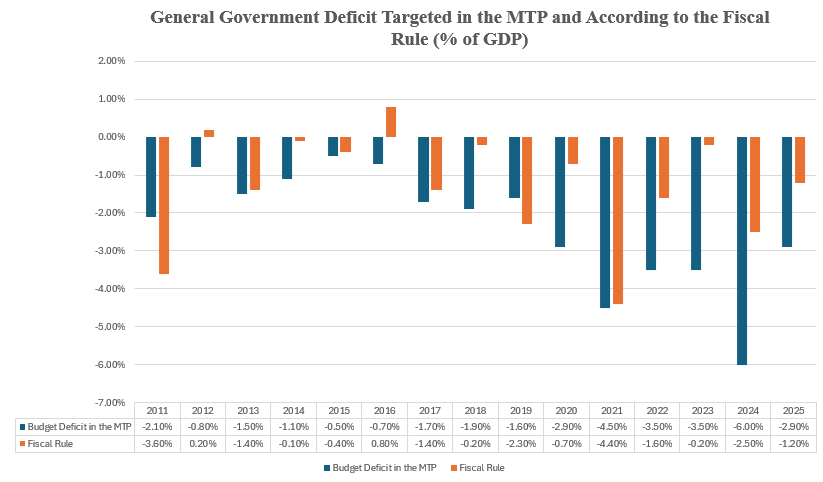

4.Fiscal Policy Objectives and Practices after the Fiscal Rule Initiative

If the 2010 Draft Fiscal Rule Law had been enacted, the general government budget balance would have been calculated according to the formula above, effective from 2011. However, the Medium Term Program (MTP) target for 2011, which was probably set based on the expectation that the Draft Law would be enacted, called for a budget surplus in 2012 according to the fiscal rule, whereas the MTP programmed a deficit of 0.8 percent of GDP. Except for a few years in the following years, there are significant deviations between the general government budget deficit calculated according to the fiscal rule and the target set by the MTP in the direction of moving away from fiscal discipline. The differences between the fiscal rule and the MTP are quite striking in some years. In 2016, the fiscal rule called for a budget surplus of 0.8 percent of GDP, while a deficit of 1.4 percent was planned. Especially in the post-pandemic period, the difference between the deficit calculated according to the fiscal rule in the bill and the figure set in the MTP reached significant levels. In fact, the 6 percent deficit projected in the 2024 budget, which was prepared after the abandonment of heterodox policies in 2023 and the transition to the traditional approach, is well above the 2.5 percent calculated according to the fiscal rule. Similarly, the deficit targeted in the MTP for 2025 is 2.9 percent, while the deficit required under the fiscal rule is 1.2 percent of GDP.

Source: MTP and my own calculations

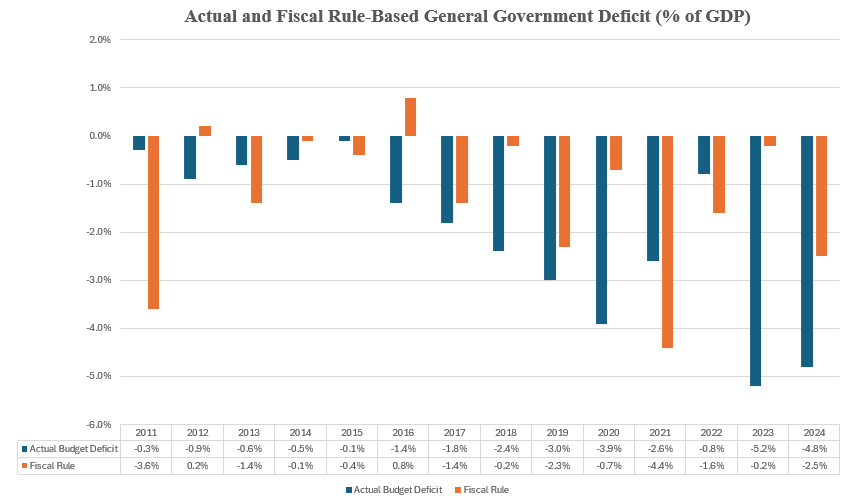

Parallel to the significant discrepancies between the targets in the MTP and the actual budget figures, the actual budget deficit also deviates significantly from the general government budget deficit calculated with the fiscal rule in the Draft Law. In this context, in the 2011-2024 period, fiscal policy has been expansionary in most years, rather than countercyclical. It is noteworthy that the budget deficit was realized many times higher than the size calculated according to the fiscal rule, especially in 2018 and 2023 when elections were held.

Source: Ministry of Treasury and Finance and my own calculations

As a result, in the aftermath of the fiscal rule that was not enacted into law, budgets were prepared and implemented without the limitations that this rule would have imposed.

On the other hand, as the calculations above indicate, the budget balance figure calculated according to the fiscal rule that supports the countercyclical fiscal policy introduced by the Draft Law varies across years. Although formulaic, the technical details that need to be taken into account in the calculation make it difficult for the less literate to understand and follow the fiscal rule.

In the same period, Serbia defined two fiscal rules for the countercyclical budget deficit and debt stock under its IMF program. The fiscal rule on the countercyclical budget deficit has important similarities with the fiscal rule proposed for Türkiye. Indeed, in Serbia’s fiscal rule formulated as (dt =dt-1- a(dt-1-d*)-b(gt-g*)), dt and dt-1 represent the budget deficit/GDP ratio in years t and t-1, d*: the ratio of the targeted long-term budget deficit to GDP, gt: the real GDP growth rate in year t and g*: the potential GDP growth rate. However, because the countercyclical budget deficit rule was considered too complex, difficult to implement, and required a minimum knowledge of mathematics and economics to understand, it was ignored by politicians and the public, and only the limit on the debt stock was considered as a fiscal rule (Begovic, Marinkovic, and Paunovic, 2016). While the Serbian experience shows the importance of simplicity and clarity in terms of the acceptance and anchoring role of fiscal rules, it also provides insight into the problems that might arise in practice if Türkiye had been able to implement the 2010 regulation.

5.The Necessity of Transition to a Fiscal Rule-based Economy in Türkiye and the Role of the Fiscal Council

Türkiye’s deteriorating budget structure and the declining effectiveness of fiscal policy in recent years have increasingly brought the need for a transition to a rule-based economy to the fore. As a matter of fact, due to the expansionary fiscal policies implemented, inflation first increased rapidly and then became sticky. Similarly, as a result of the expansionary fiscal policies implemented in many countries, particularly in the US and EU countries after the 2008 crisis, serious deterioration in the fiscal indicators of these countries emerged and even the limits stipulated by fiscal rules were exceeded. In this context, countries took some measures (Karayazı, 2017):

– Revision of Rules: Some countries have relaxed existing fiscal rules or added new parameters, taking into account the extraordinary circumstances created by the crisis. For example, debt stock and budget deficit limits were temporarily raised, but structural reforms were planned to ensure discipline in the long run

– Suspension of Rules: At the height of the crisis, countries such as Spain and Greece suspended fiscal rules altogether and resorted to extraordinary spending and borrowing policies. This was adopted as a temporary solution until economic recovery was achieved

– Addition of New Rules: Some countries have introduced new regulations in addition to existing rules. For example, in Germany, the “Debt Brake Rule” (Schuldenbremse) was adopted at the constitutional level in 2009, limiting the federal government’s structural budget deficit to 0.35% of GDP.

Considering that the main function of fiscal rules is to enforce fiscal discipline by limiting flexibility in political decision-making processes, it is not enough to impose numerical limits on elements of public finance such as revenues, expenditures, borrowing and financial liabilities; it is also necessary to establish an institutional structure for the implementation of these rules and the credibility of fiscal policy in general. Indeed, the crisis exposed weaknesses in public finances and led governments in many countries to undertake institutional reforms to enhance fiscal discipline and credibility. In this context, fiscal councils have emerged as an important element to ensure credibility by making independent assessments of fiscal policies and fiscal forecasts (Hagemann, 2011).

Fiscal councils are non-partisan, technical bodies tasked with various duties as public finance watchdogs to strengthen the credibility of fiscal policies. The IMF (2013) defines a fiscal council as “a permanent legally mandated institution tasked with assessing the government’s fiscal policies, plans, and performance in a transparent and non-partisan manner, taking into account macroeconomic objectives related to the long-term sustainability of public finances, medium-term macroeconomic stability, and other official objectives”. Fiscal councils are non-partisan, administratively independent public institutions whose mandate includes assessing medium-term fiscal plans and the performance of governments in this context, making independent assessments of macroeconomic targets and budget forecasts, monitoring the implementation of fiscal rules, monitoring the government’s implementation of corrective measures when necessary and determining the sustainability of public finances by determining the costs of these measures, and helping to improve fiscal transparency and promote fiscal stability. In addition to their function of monitoring the fiscal rule, fiscal councils often contribute to the formulation of fiscal policy, make macroeconomic assessments and analyze economic policies. In addition, fiscal councils contribute to enhancing the credibility of fiscal policy and governments in general due to their role in preventing populist preferences and commitments that may put medium and long-term fiscal sustainability at risk and limiting the costs that may arise in this context (Davoodi et al., 2022).

In Türkiye, as in the rest of the world, it is common for governments to tend to stretch their medium-term public finance targets due to short-term priorities indexed to electoral periods, leading to significant and permanent deviations from time to time. Therefore, the implementation of a fiscal rule based on the budget deficit and the ratio of government debt to GDP, in line with international practices, is considered essential to ensure the effectiveness of fiscal policy. In addition, the establishment of a fiscal council as a non-partisan and independent technical body with various powers, which will be assigned as a public finance watchdog, will strengthen the credibility of fiscal policies.

In 2010, the existence of fiscal councils, which were not included in the draft law but have been implemented in many countries in the post-2008 period, strengthens the anchor function of fiscal rules and helps to improve transparency and promote fiscal stability. According to the IMF’s fiscal rule dataset, the number of fiscal councils doubled after the 2008 crisis. Indeed, as of 2021, 49 countries have fiscal councils.

6.Conclusion

One or more fiscal rules, which include numerical targets and corrective measures in case of deviations from these targets through a permanent legal arrangement secured by the Constitution or higher legal norms, serve as an anchor to enhance the effectiveness not only of fiscal policy but also of economic policy in general. In fact, international practices point to the expediency of fiscal rules that are defined in terms of budget deficit and debt stock and that are simple and easily monitored by the public. On the other hand, fiscal councils have been introduced in an increasing number of countries to strengthen the anchor feature of fiscal rules in pursuing medium and long-term objectives, such as fiscal sustainability, given the short-term priorities of governments. In fact, fiscal councils, which ensure the functioning of fiscal rules, have become increasingly widespread around the world and have doubled in number over the past decade.

In Türkiye, Article 5 of Law No. 4749 established a borrowing limit that cannot be changed by supplementary budgets in order to ensure discipline in public finance and budget execution. However, the borrowing limit, which was increased five times in the 2017-2023 period through temporary articles added to Law No. 4749, has become virtually dysfunctional. In this context, it is understood that the borrowing limit alone is insufficient to achieve medium and long-term fiscal targets and to ensure fiscal sustainability. In this context, in order to achieve the medium- and long-term objectives of fiscal policy, such as stability, efficient allocation of resources and fairness in income distribution, it is deemed imperative to adopt a rule-based public finance model in which short-term priorities and populist preferences will not put medium- and long-term fiscal sustainability at risk and transparency and accountability as well as predictability will increase.

Considering that the borrowing limit, which is a constraint to ensure fiscal discipline, is frequently changed, it is important that the fiscal council, as an independent technical body that monitors fiscal rules, reports budget performance to the public, and evaluates the government’s macroeconomic targets and budget forecasts, be incorporated into public financial management as a legal and permanent structure.

In light of these considerations, in addition to the borrowing limit in Law No. 4749, in the short term, an amendment to Law No. 5018 would establish fiscal rules that ensure medium and long-term sustainability, including the budget deficit and debt stock, and the establishment of an independent fiscal council, preferably within the TGNA, to monitor these fiscal rules would eliminate uncertainties arising from fiscal policy and ensure that public financial management is in line with the principles of transparency and accountability.

References

Aktan, C.C., D. Dileyici ve A. Özen. (2010). Kamu Ekonomisinin Yönetiminde İki Farklı Ekonomi Politikası Yaklaşımı: İradi ve Takdiri Kararlara Karşı Kurallar, içinde C. C. Aktan, A. Kesik., F. Kaya (Eds.) Mali Kurallar. Maliye Bakanlığı Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı Yayın No 2010/408. Ankara.

Beetsma, R. ve X. Debrun. (2018). Independent Fiscal Councils: Watchdogs or lapdogs? VOXEU, CEPR. https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/60158-independent_fiscal_councils_watchdogs_or_lapdogs_.pdf

Begovic, B., T. Marinkovic, M. Paunovic. (2016) A Case for Introduction of Numerical Fiscal Rules in Serbian Constitution. FC Research Paper 16/02 http://www.fiskalnisavet.rs/doc/istrazivacki-radovi/A_case_for_introduction_of_numerical_fiscal_rules_in_Serbian_constitution_FC_reseach_paper.pdf

Cangöz, M.C. (2019) Borç Yönetiminin Kurumsal Yapısı: Nereye Gidiyoruz?, TEPAV Değerlendirme Notu N201929. Türkiye Ekonomi Politikaları Araştırma Vakfı, Ankara. Erişim adresi: https://www.tepav.org.tr/tr/haberler/s/10033

Cangöz, M.C. (2021) Orta Vadeli Program ve Gelecek Üç Yıllık Dönemde Kamunun Mali Duruşu, TEPAV Değerlendirme Notu N202127. Türkiye Ekonomi Politikaları Araştırma Vakfı, Ankara. Erişim adresi: https://www.tepav.org.tr/tr/haberler/s/10349

Cangöz, M. C. (2022). Devletin Borcu İçin Dertlenmeli miyiz?, TEPAV Değerlendirme Notu N202227. Türkiye Ekonomi Politikaları Araştırma Vakfı, Ankara. Erişim adresi: https://www.tepav.org.tr/tr/haberler/s/10480

Davoodi H. R., P. Elger, A. Fotiou, D. Garcia-Macia, X. Han, A. Lagerborg, W.R. Lam, and P. Medas. (2022). Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Performance during the Pandemic. IMF Working Paper No.22/11, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/Working%20Paper%20-%20Fiscal%20Rules%20and%20Fiscal%20Councils%20-%20Recent%20Trends%20and%20Performance%20during%20the%20Pandemic.pdf

Hagemann, R. (2011). How Can Fiscal Councils Strenghten Fiscal Performance. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, volume 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-v2010-1-en

International Monetary Fund. (2009). Fiscal Rules—Anchoring Expectations for Sustainable Public Finances. December 2009. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2009/121609.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2013). The Functions and Impact of Fiscal Councils. July 2013. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/071613.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2022). Fiscal Rules Dataset 1985-2021. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/map/map.htm#:~:text=A%20fiscal%20rule%20is%20a,fiscal%20responsibility%20and%20debt%20sustainability.

International Monetary Fund. (2022). Fiscal Council Dataset. https://www.imf.org/en/Data/Fiscal/fiscal-council-dataset

Karayazı, M. (2017). Küresel Krizin Mali Kural Uygulamalarına Etkisi: Seçilmiş Ülke Örnekleri Açısından Bir İnceleme. Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi Cilt 10 Sayı 51 1047-1058 http://dx.doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2017.1836

Kopits, G. ve S. Symansky. (1998). Fiscal Policy Rules, IMF Occasional Paper 162. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781557757043.084

OECD. (2013). Fiscal rules in Government at a Glance, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-26-en

Schick,A. (2010). Post-Crisis Fiscal Rules: Stabilising Public Finance while Responding to Economic Aftershocks. OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol.10/2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/budget-10-5km7rqpkqts1